Your basket is currently empty!

‘Loading’ in the Golf Swing

A players interaction with the ground facilitates the generation of torques, rotations and velocities in the golf swing. One would not generate much clubhead speed while floating about in space! Swing theory in this regard appears to have progressed through three discrete phases over recent decades. I am not a golf historian; consider the following then as more of an impression, rather than strictly chronologically accurate. Anyway those three stages can approximately be defined as follows:

- Weight transfer / shift (pre 1990s)

- Weight loading (Leadbetter et al, mid 1990s – early 2000s)

- Joint loading (circa last 10-15 years)

Semantics wise at least, the first two of the above are problematic. The first (transfer / shift) could be taken to imply ‘a lateral shift of mass away from the target’. The second, one could easily imagine might encourage excessive hanging onto one’s trail side. The third is much better descriptively. It removes the notion of the players mass or even centre of mass entirely, substituting primarily for vertical forces. Namely, the oppositional affects of ‘ground reaction force’ (GRF).

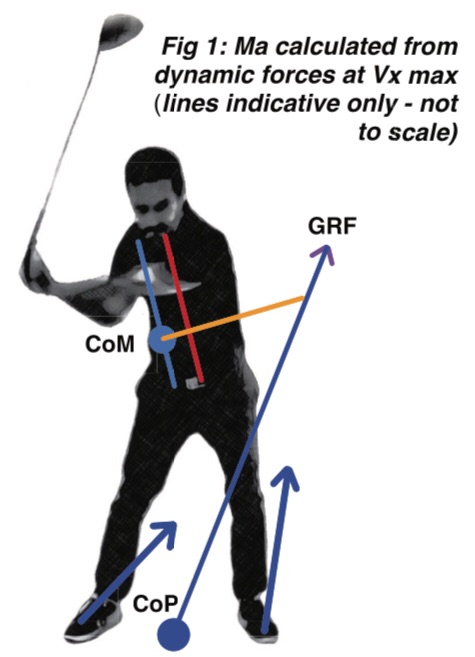

Nevertheless, centre of mass (CoM) is crucial to the generation of torque and therefore ultimate clubhead speed. Of particular import, is its’ location medial-laterally (trail or lead side) at various points in the swing. The primary predictor of torque is the length of the players moment arm (Ma). (Moment arm is the orange line in the above image.) Of critical importance, you can see Ma is measured from the players CoM. All other things remaining equal then, during the downswing a more trail-ward CoM lengthens Ma, amplifying resultant torque. But…

‘consciously trying to move CoM laterally is unreliable. It can all too easily lead to lateral shift or sway, on and off of the ball.’

CoM should be manipulated via correct dynamics and sequencing only and thus should pretty much take care of itself. Long drive competitors often focus on the vertical component of weight or mass shifts, over the lateral. For normal competition golf, accuracy is just as important, if not more so than distance. For this reason I would suggest that in the main, forgetting about CoM altogether is a pretty good idea.

It is a common misconception that ‘full loading’ occurs at the top of the backswing. This is incorrect and possibly a manifestation of the trend to sit or squat into the backswing, as popularised a few years back. Loading (of a joint) is a consequence of GRF. In physics parlance GRF is (loosely) defined as the force of the ground pushing upwards, in static equilibrium to the players dynamic mass. Looking at GRF traces of elite players atop of force plates then, what may surprise you is that…

‘ground reaction reaches maximum in the backswing when the lead arm is parallel to the ground.’

Thus, there is actually no requirement to hang trailward. There exists no reason to increase pressure (or ‘weight load’) under the trail foot excessively throughout the backswing. Subsequently, during the downswing maximum GRF occurs roughly as the club shaft orientates parallel to the ground. By this point GRF has moved lead-ward. By impact the lateral component of lead foot GRF vector may actually be traveling away from the targey.

So what is to be taken from this? Two things I would say are of upmost importance, at least initially when considering swing changes.

- Firstly, the ability to recognise force traveling vertically upwards into the pelvis trailside in takeaway.

- Secondly, avoiding consciously shifting mass around during the golf swing in general.’

I truly believe that sound swing dynamics requires a base understanding of muscle physiology, in a mechanical and dynamic sense. It is crucial to know what musculature does what and when, in terms of the required biomechanics. Also, one requires some appreciation of the physics involved. Centre of pressure (CoP) is for another day, but changing the location and direction of CoP (for reasons discussed in the book) is far more effective in generating torque than Com. It encourages far less mediolateral displacement (sway) also.

‘Shifting centre of pressure (CoP) around in the golf swing is very different to shifting centre of mass (CoM).’

Mimicking, positional rehearsal and repetition is commonplace in contemporary golf coaching. I don’t believe that in isolation this is either the easiest, or most efficient modality of learning for most. It fails to give a sense of the forces and dynamism involved. The swing is a dynamic process, thus should be learned as such. My undergraduate degrees was actually Psychology. I can say with some certainty then, that for a particular type of learner, this methodology will be pretty much fruitless. At least for a minority subset of golfers, it will fail in terms of maximising potential. Which is what led me to write ‘The Physics and Biomechanics of Golf’ in the first place.

If you have, thank you ever so much for taking the time to read this blog.

All the best.

Discover more from golfbiomechanics.net

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Comments

3 responses to “‘Loading’ in the Golf Swing”

Great article. As a “feel” player your point about “vertical torque” in the musculature really resonates. In the early takesway Ive been concentrating on staying more centred and not swaying to the trail side (previous flaw causing block right). Whith this staying centred the torqe builds early in the takesway on the inside of the trail leg and rises up to the hips and pelvis. The shoulder turn then feels like torque is added to the abdominals, obliques and latimuss dorsi. This torque then unwinds the upper body with its oppising force which trasfers vertically down into the trail instep proving kind of “push off” feeling.

Thanks for the feedback. 👍 I am glad the article rang true for you. Couple of points that may help you:

– If you struggle to curtail sway in takeaway, in practice try activating your trail femoral adductor as your torso moves the club away. The femoral adductors are the muscles that people who use a ‘Thigh Master’ are actually working. They move the leg (femur) towards the body centreline.

– From the top you should re-centre, transiting onto your lead foot, so maybe focus the opposing force downward under your lead instep not the trail.

– The trailside does support pivot through impact (at least that’s what the research seems to suggest), but prior to this the ‘push’ off of the lead leg should have assisted the lead oblique and driven the lead hip back in pivot.

Hope helps and all the best.…and as if by magic this was just posted by the Titleist Performance Institute!

https://x.com/MyTPI/status/1878898889111306513?t=7EYsZuOvdCetwoCyFeaLjw&s=19

Maybe we have been hacked.🤣

I haven’t watched the video yet, but sounds like it may be helpful to you.👍

Leave a Reply