Your basket is currently empty!

Vertical Force in the Golf Swing

I am having a weeks break from the series ‘Sequencing in the Golf Swing’. This blog was brought about by a discussion I had this week on ‘X’ pertaining to the question. With respect to the golf swing…

‘…what is vertical force?’

That’s an easy one, smashing, I know that one! 👍

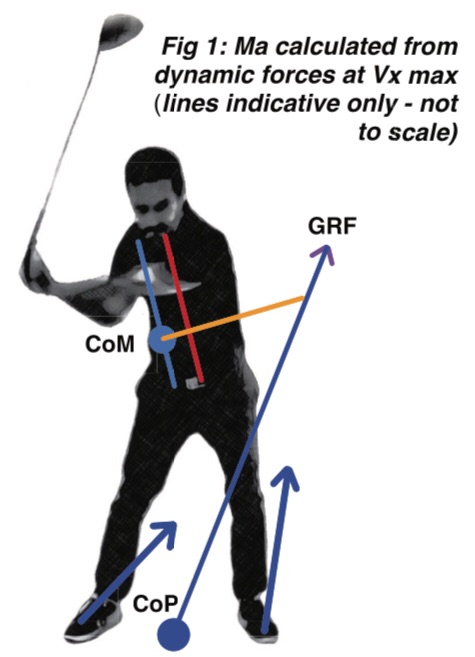

It is ‘ground reaction force’ or GRF, which is the upward force exerted statically by the ground. Its’ force is in equivalence to the weight positioned upon it. (More correctly the mass upon it, as the golf swing being dynamic creates momentum). The energy from GRF is transferred into the torques and resultant accelerations in the golf swing. Great let’s all move on. What, wait… there’s more!

‘…explain vertical force in (the) golf swing. I cannot figure out how it helps ball flight…’

Oh blast, it’s going to be a long night after all then!😖

This is such a salient question. It encapsulated the disconnect between the physics, biomechanics, instruction and the observed golf shot. By now I think GRF has pervaded the vernacular of most coaches. It is and has been widely understood for decades now. It is not the end-all with respect to generating speed though, which I think is sometimes overlooked.

José Luis Ballester, winner of the 2024 US Amateur, subsequently making the cut at The Open, has prodigious clubhead speed. Analysis has shown him to have relatively low GRFs compared to his peers and contemporaries. He achieves this club speed primarily through ‘lag & release’. It probably is not surprising to learn that he is coached by Victor Garcia, Sergio Garcia’s father.

Vertical force can be employed or deployed to generate vertical, horizontal or angular momentum. One can pivot, sway or rise in reaction to this force. All three of these are required during the golf swing, but the first two, very much in moderation. Redirection of the global GRFs’ centre of pressure (CoP), is more reliable than shifting center of mass (CoM) via sway. The requirement for horizontal & vertical shifts, is extremely limited. Coaches spend swathes of their time trying to curtail these tendencies. It is also possible to have too much hip and torso rotation in a sense. Especially so, if other dynamics and sequencing are incorrect or non-synchronous in some way.

Within the ‘X’ exchange I mention, there were a couple of unusual but valid points being raised by all parties. They contradicted one another in a certain sense, but only because each side had its own context. Referencing long drive competitors, it was noted how vertical forces can result in quite extreme vertical displacements. Long drive competitors for example often jump vertically and posteriorly off of their lead foot. They may practice drills that encourage extreme descent of the upper torso around transition. These must then be rebounded from to create adequate vertical space.

The second context was a player that prescribes to a ‘rotate, lag and release’ type philosophy. In an ideal scenario, hitting driver you would yield maximum leverage, so create a zero lag condition at impact. This then renders the three levers of the upper arm, lower arm and club a straight line. Effectively then, these become a single lever. The butt of the handle rises vertically in rotation to meet this condition. It was posited, vertical force is used to achieve this. Thus the player creates a small amount of required ‘vertical space’. This might be achieved via extension in opposition to some of that predominantly vertical GRF.

The final context was the observation of the fault of ‘early extension’ (of the pelvis). This is apparent in the swings of so many club golfers, sometimes even a vertical shift of the hips themselves. I would consider this to be far and away the most common misapplication of vertical force. As explained in ‘The Physics & Biomechanics of Golf’, extending the pelvis can only be achieved by the stricture of pivot. Primarily pivot is provided by the lead external oblique, which is shut off by pelvic extension. This is disastrous in terms of generating clubhead speed.

‘Vertical force if employed correctly plays a significant contribution to clubhead speed and energy transferred to the ball.’

The point was that all three of these observations are correct from their given perspectives. But how should vertical force be used in swing improvement. I would consider it quite risky to employ GRF to rehearse any form of vertical rise, excluding the ‘followthrough’. That is, unless there exists a specific deficit in this regard. So with all that in mind, here was the last part of my response to the post…

‘…you could think of opposing the GRF with the lead quad mid downswing, to extend the lead knee and drive the lead hip back in pivot, thus avoiding the vertical pelvis displacement you mention.’ Hope helps. 👍’

As lag is given-up midway down, angular momentum starts to decrease. Therefore pivot must be supported, first off of the lead side, then via trailside extension through impact. Of course this is just one aspect of a whole. To be able to make a late phase articulation such as described above requires correct dynamics prior. Therefore I had better get cracking on ‘Sequencing Part 2’ for next weekends blog.

As always, if you have, thanks ever so much for taking the time to read this blog.

All the best.

Discover more from golfbiomechanics.net

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply