Your basket is currently empty!

The Hands in the Golf Swing Part 2

Minimising hand and wrist involvement if the golf swing

‘The hands should have little if any involvement prior to the lead arm being vertical to the ground in the backswing’.

So how does this work exactly? How does the clubhead move away in advance of the hands with minimal hand or wrist involvement? The answer…

‘…intra humeral rotation largely moves the club and also controls rotation of clubface.’

This motion is independent of, and in addition to the momentum provided by the pivot of the upper torso about the cervical spine.

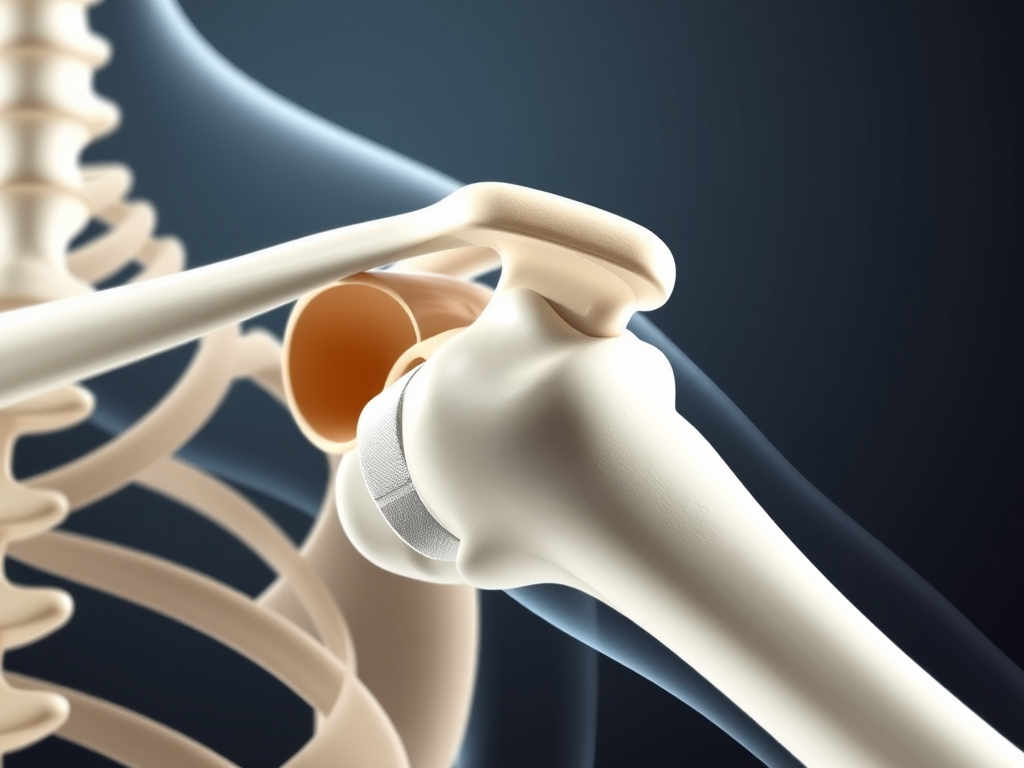

The shoulder is a ‘ball and socket’ type joint, unlike the elbow, a primarily ‘hinge’ type joint. This gives the humerus three available axis of motion within the shoulder (glenoidal) socket. These are: away and towards the body, across or to the side of the body and internal or external rotation. The scapular can also raise and lower and / or project and retract. As you can see then, the shoulder has five degrees of freedom. For the takeaway only one of these is required, that being, intra-glenoidal rotation of the humerus.

That intuitively may not seem correct. After all…

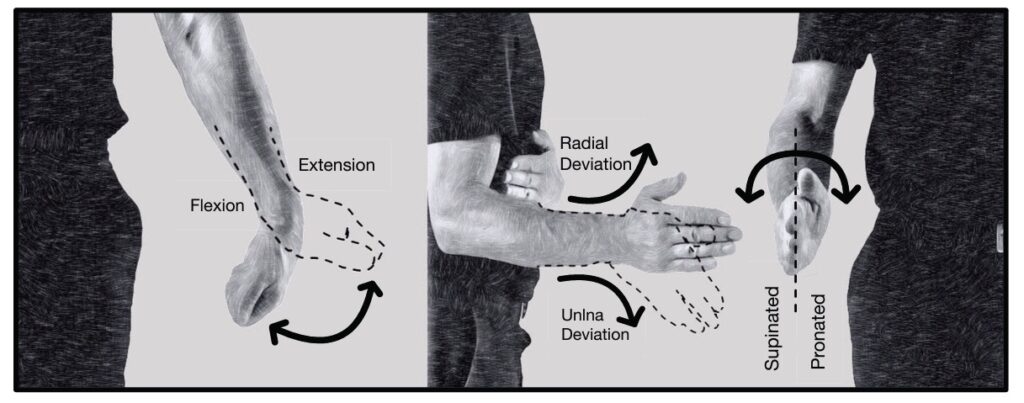

‘…the clubhead moves along 3 separate axis in takeaway: away from the target, upwards and also rearwards. What makes this possible is radial deviation of the wrist, or put another way, the longitudinal angle between forearm and the club shaft.’

Try the following exercise…

1). Grip a club with your trail hand (right hand for right-handed golfers). Stand in posture and raise the clubhead vertically off the ground by bending the wrist upwards (radial deviating). Now rotate your arm rearward (external rotation).

Completing the backswing, the last axis of motion (upward), is supplied via pivot of the torso about the upper (cervical) spine. Width is provided by the arm moving trailward (adduction). But these are not prevalent or necessary in the takeaway. Best of all, the radial angle of the wrist is set in advance as it is in the golf swing. In ‘The Physics and Biomechanics of Golf’, I emphasise how the wrists should be curtailed, especially wrist extension. For the trailside, ‘wrist extension’ describes the cocking of the hand away from the target. In the backswing wrist extension is largely unnecessary. In the downswing it is often confused as the source of ‘lag’. Worse still wrist extension makes it extremely difficult to introduce or maintain radial deviation.

The above biomechanics limitation is why golfers who get ‘wristy’ from transition often whip the club on the inside. This may lead them to describe a ‘figure of eight’ type clubhead path away and back down. Go back to the exercise above’s starting position and now try the following.

2). Instead of lifting the club off of the ground vertically, ‘cock’ the trail hand rearward into extension. The club will travel low and rearward when extension is made the the source of clubhead motion. Hold the resultant position. Attempt to pull the wrist up into radial deviation from here. Without any forearm rotation (which as we discussed in Part 1, should have little involvement at this juncture). This motion is all but impossible.

3). Now make your torso pivot to the top of the backswing. If you haven’t picked the club up steep in the second phase, the club will be far too low. It will almost certainly also be way behind you.

By introducing deliberate wrist extension, you may also need to introduce extraneous shoulder flexion or other artistic motion to compensate. By this point you will be noticing a theme. ‘Less is more’ when it comes to hand articulation in the golf swing. If this was obvious and overt, excessive hand involvement wouldn’t be so prevalent in the golf swing.

There exist numerous dynamic drills available to counter extraneous tendencies, some of which are introduced in the book. In ‘Part 1’, I hinted at the benefits of dynamic drills without a golf club. The primary reason a baseball bat is useful in this sense, is because of its’ mass. The following extract is taken from the summary to ‘Chapter 1: Forces and Fundamentals’.

‘A similar description could be given to swinging a sledge-hammer. Is thousands of hours of practice and copious tuition required? No, even if attempting to swing the hammer on an inclined arc. This is because, in a way biomechanics are enslaved, dictated by the mass and so effort involved, we have no choice but to be mechanically efficacious with technique. Employing the ‘three fundamental’ approach to golf learning follows this chain of logic.’

I hope you are having a happy Christmas Day. In ‘The Hands in the Golf Swing Part 3’, lag and impact conditions will be explored.

All the best.

Discover more from golfbiomechanics.net

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply