Your basket is currently empty!

The Hands in the Golf Swing Part 1

The hands relationship with ‘shoulder rotation’, the forgotten mechanic

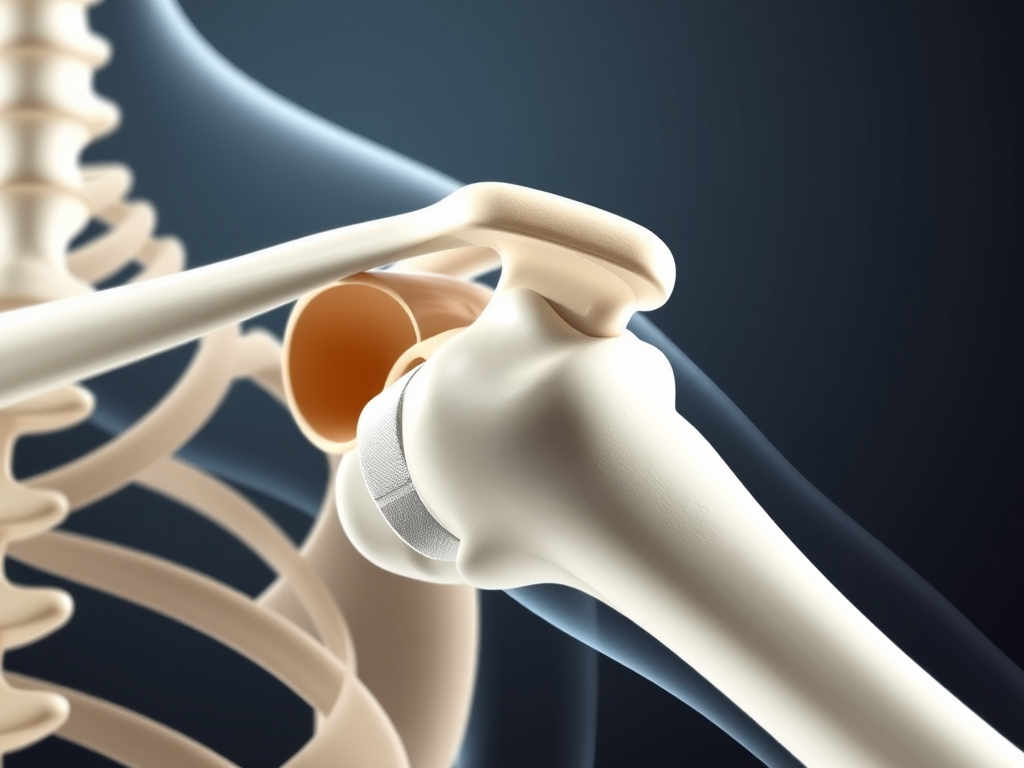

Humeral rotation is uniquely important to the mechanics of the swing, yet chronically overlooked in golf instruction. Rotation within respective shoulder sockets (glenoidalis) determines many aspects of the golf swing including: swing plane, the club face’s relationship to path and top of the backswing. In addition it plays a significant role in swing dynamics generally. It is incredibly important. Why is this and other shoulder articulations so readily overlooked?

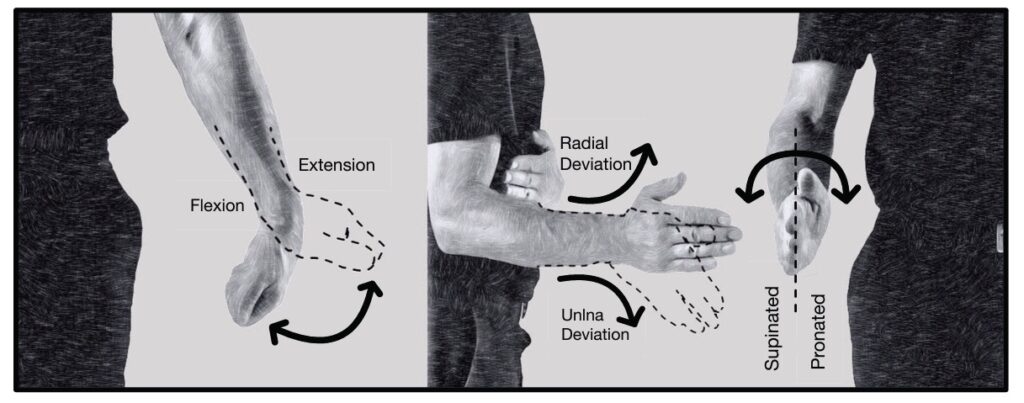

Unrepresentative focus on wrist articulation answers this question, as well as some general misunderstandings with relation to biomechanics and dynamics. When describing hand or wrist motion in the golf swing, there exist three distinct articulations (see diagram below). Of these, generally supination & pronation are given much more ‘air time’ than is rightly deserved, certainly in isolation.

Supination and pronation are slight misnomers with respect to swing mechanics, describing rotations of the forearm, as articulated via the elbow joint.

‘In actuality, with respect to the takeaway, humeral rotation within the shoulder sockets proactively dictate longitudinal rotation of the hands.’

The upper arm and forearm do rotate independently, but the velocity of change in angular orientation between wrist and elbow stays fairly constant throughout much of the swing. The speed at which this angular relationship changes is not linear, but is stable for much of the swing nonetheless.

Let’s consider the trail hand. Although a little under half of the clubface rotation in the backswing (circa 90 degrees) may come from supination, this is at the behest and subject to freely available humeral rotation. So, forearm rotations increases near the limits of shoulder mobility range. This notion then, reduces the import of the wrists and hands, at least for much of the golf swing.

‘The less that wrists and hands are involved in the golf swing, the easier it becomes.’

Look online at a ‘golf robot’ hitting balls for evidence. Mechanically simpler is better – ‘added simplicity’ being a key premise for ‘The Physics and Biomechanics of Golf’. The more hand axial mobility available via the shoulder then, the less hand, wrist and elbow involvement required. Inter-glenoidal humeral rotation is a key metric in ‘Titleist Performance Institute’ testing, and I guess for good reason. (In the book I describe how you can test this yourself, in a more golf relevant way than typically employed elsewhere.)

How is this information useful then? Well, as noted forearm rotation should ramp-up when shoulder rotation is towards the end of its range. In the golf swing this occurs toward the top of the backswing and completion of the follow through. Despite what you probably rehearse in your ‘waggle’…

‘…hands should neither motivate nor set the path, or dictate rotation of the clubface during takeaway.’

Exclusively this is the job of cervical (upper spine) rotation and shoulder articulation. (Going back to Ben Hogan’s seminal book, the waggle was intended to release hand tension, not to rehearse the takeaway). Hopefully this makes it clear why so many golfers (including myself) suffer either from picking the club up too steep, whipping it inside too shallow, or too fast, etc.

‘The hands should have little involvement prior to the lead arm being horizontal to the ground in the backswing.’

What happens after that (with respect to pronation / supination) should be autonomic in any case. To what extent this is communicated in golf instruction I wonder? I have certainly never given shoulder motion a rotation much thought.

In the book I focus extensively on proprioception (sensory awareness) and the many overlooked dynamics and mechanics. First amongst these is shoulder rotation. This is where takeaway focus might be, were the golf swing not learned in the systematic way it is. Specifically putting precedence on hands, via over prioritisation of the grip and clubhead. Dynamics should come first. You don’t need to be holding a golf club to develop excellent golf dynamics. A perfectly good motion and swing mechanics are attainable gripping a baseball bat with a two-handed ‘baseball grip’ for example. In fact, this is in many ways easier as will explained.

More to follow in ‘The Hands in the Golf Swing Part 2’. If you have, thanks for taking the time to read this blog.

Have a very happy Christmas.

Discover more from golfbiomechanics.net

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply